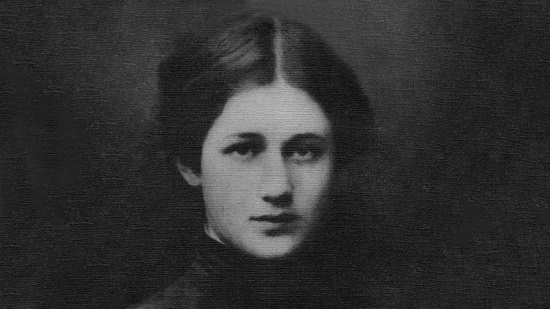

25 interesting facts about Anna Akhmatova

The poetess Anna Akhmatova lived a hard life. She was actively persecuted, prevented from being published, and her relatives were persecuted and persecuted. Her work reflects all the suffering through which not only people passed whom the ruling party considered “enemies of the people”, but also their families. Even after the death of the poetess, her works were not printed for a long time, and she was rehabilitated only a long time after she was gone.

The poetess Anna Akhmatova lived a hard life. She was actively persecuted, prevented from being published, and her relatives were persecuted and persecuted. Her work reflects all the suffering through which not only people passed whom the ruling party considered “enemies of the people”, but also their families. Even after the death of the poetess, her works were not printed for a long time, and she was rehabilitated only a long time after she was gone.

She herself called herself a poet, not a poetess. The word “poetess” Anna Akhmatova could not stand, and she was very angry if someone called her that.

Anna Akhmatova is a pseudonym, her real name is Gorenko. But her father was categorically against her daughter’s hobby for literature, and forbade her to use her family name.

Akhmatov’s whole life was embarrassed by his first work. Early ballad poems, published, reprinted, and very popular, she called “poor poems of the empty girl”, and did not like to remember them.

One day, while walking in the garden of Tsarskoye Selo, she found a pin in the shape of a lyre. All her life, Anna Akhmatova believed that A.S. Pushkin himself once dropped this pin here.

Anna grew up in an unusual family. There were almost no books in the house, although her mother knew by heart many poems of Derzhavin and Nekrasov. This is probably partly why she was interested in literature from childhood.

A brief biography of Anna Akhmatova reflected that in childhood she suffered a serious illness, presumably smallpox, the disease left her deaf for a while, and it was after recovery that she began to write poetry.

In the spring of 1910, the Italian artist Modigliani met in Paris with a very young, but already married Anna Andreyevna. Romance lasted until August 1911, after which they never met again. However, this time gave the artist so much inspiration that over the year he painted many paintings, devoting them all to his beloved.

The poetess survived two World Wars, and her two husbands and son were repressed after the revolution in Russia.

She tried with all her might to save her sent son, Lev Gumilyov, and even wrote a series “Glory to the World” glorifying Soviet power, but all her attempts were unsuccessful. Her son was released in 1943, but was rehabilitated only in 1956, and he accused her mother of inaction, which was a severe blow for her.

According to Anna Akhmatova’s own memoirs, she was a “wild girl”, loved to walk barefoot and swam in the sea in any weather. Such behavior for a young lady in that era was considered unacceptable.

Already in childhood, the poetess at a high level mastered the French language.

In 1939, she was admitted to the Union of Soviet Writers, from where she was expelled in 1946, and five years later restored.

Anna Akhmatova was twice nominated for the Nobel Prize in literature, in 1965 and in 1966, but this became known only after 50 years. It turned out that the candidacy of Akhmatova was put forward by professors of Slavic languages Gunnar Jacobson from the University of Gothenburg and Roman Jacobson from Harvard.

Akhmatova composed her first poem at age 11. After rereading it “with a fresh mind”, she realized that she needed to improve her art of versification, which she began to actively engage in.

The year before her death, in 1965, Anna Akhmatova visited the UK and became an honorary doctor at Oxford University.

Throughout her life, she kept a diary. However, it became known about him only 7 years after the death of the poetess, when he was accidentally discovered.

In addition to composing her own poems, A. Akhmatova was also involved in translating foreign poetry into Russian.

Recognized as a classic of Russian poetry back in the 1920s, Akhmatova was silenced, censored and persecuted. At the same time, during her lifetime, her name was surrounded by fame among admirers of poetry both in the USSR and in exile.

In the USSR, many of her works were not published not only during the life of Anna Akhmatova, but also about twenty years after her death.

The last collection of poems by Akhmatova was published in 1925. After that, the NKVD did not miss any of the poet’s works and called him “provocative and anti-communist”.

For a long time, the poetess was under the supervision of the NKVD. Researchers of the biography of Akhmatova believe that the writer Sofia Ostrovskaya, who the poet considered her close friend, not knowing that she works for the NKVD, was following her.

The poet’s first husband was later repressed Nikolai Gumilyov, who long sought her hand. Moreover, none of his relatives came to the wedding – they were all against this marriage, and believed that he would not drag out for a long time.

In honor of the poetess, the streets in Kaliningrad, Odessa and Kiev are named. In addition, on June 25 each year in the village of Komarovo, Akhmatov’s commemorative evenings dedicated to Anna Akhmatova’s birthday are held.

The poetess also wrote literary articles, very serious and deep. They were mainly devoted to the work of Pushkin and Lermontov.

Akhmatov’s whole life was very superstitious. So, at first she refused to Gumilyov, asking her hands, because during a walk along the beach they stumbled upon two dolphins that had washed ashore. The poetess considered this a bad sign.