Great Northern Expedition

In the 16th and 17th centuries, boats of Russian coast-dwellers and merchants often went from the White Sea and Pechora to the mouths of the Ob and Yenisei. There is information that they went there even earlier than the squad of Ermak penetrated into the Siberian expanses beyond the Urals. It is possible that some brave souls penetrated far into the “Cold Sea”.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, boats of Russian coast-dwellers and merchants often went from the White Sea and Pechora to the mouths of the Ob and Yenisei. There is information that they went there even earlier than the squad of Ermak penetrated into the Siberian expanses beyond the Urals. It is possible that some brave souls penetrated far into the “Cold Sea”.

Traces of such bold travels dating back to the beginning of the 17th century were found even at the northern tip of the Taimyr Peninsula. They say that the Russian vessel passed around 1620 past Cape Chelyuskin, the extreme northern point of the Euro-Asian continent.

Long journeys were also made from the mouths of other rivers of Siberia: Khatanga, Lena, Indigirka, Kolyma. Cossacks distinguished themselves in these journeys: Elisey Buza, Ivan Rebrov, Mikhail Stadukhin, Fyodor Chyurka, Timofey Buldakov and many others. In 1648, on the way to the Pacific Ocean, industrialist Fedot Popov and Cossack Semyon Dezhnev and their comrades sailed across the Chukchi Sea east of Kolyma. In this voyage, the last of the unknown parts of the sea coast was bypassed and the strait between Asia and America was opened.

Unfortunately, not all of these journeys and discoveries became the property of the science of that time. Participants did not always describe them. Historians are searching for clumps of information about these voyages in various archives among trade reports, reports on tax collection and petitions with requests from “serving people”.

Some of them became known only during the Great Northern Expedition, when the scientists who took part in it reached the dusty archives of the offices of some Siberian cities.

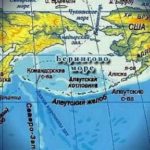

In the 16th and 17th centuries there was no general idea of the shores of the ocean, but many parts of it were well known to mariners and even depicted in drawings. At the beginning of the 18th century, the government conceived works for the purpose of more accurate surveying of the seas of Russia.

The scale of the expedition was enormous. It was attended by thirteen ships and a number of small, auxiliary. Its personnel numbered about six hundred lower ranks and officers. In the annals of history it is preserved under the name of the Great Northern Expedition. She acted for eleven years.

The delivery of people, food and equipment to the place where the troops were based was fraught with difficulty and was carried out for many thousands of kilometers by horse-drawn transport and on foot. Ships were built on rivers. In the spring they descended to the mouth and went out to sea for work.

In those years when the Great Northern Expedition was working, the winters were especially cold, with bitter frosts; and in the summer, heavy ice was long preserved along the coast, without launching ships at sea. Even the stretch of coast between Arkhangelsk and the mouth of the Ob was difficult to reach. The detachment headed by S. Muravyov and M. Pavlov, and then S. Malygin, had to return several times from the Kara Sea, not reaching the target due to ice. But the sailors did not give up. And after four years, their efforts were crowned with success, – they circled the Yamal Peninsula and passed at the mouth of the Ob River.

D. Ovtsin filmed the area between the Ob and the Yenisei on the Tobol dubbol. In 1734 he managed to pass in the Ob Bay up to a latitude of 70 ° 4 ′; the following year, the campaign was unsuccessful due to the illnesses of the crew; In 1736, Tobol reached a latitude of 72 ° 34 ′, where it was stopped by heavy ice. In 1737, D. Ovtsin managed to go to sea, go around Cape Mate-Sale and enter the Yenisei Gulf. Thus, it took four years to shoot this plot too.

The conditions on the site of the Taimyr Peninsula and its northern tip, which is the northernmost point of the continental land on our planet, proved incomparably more difficult.

The history of the discovery of Cape Chelyuskin is rich in vivid episodes of human fearlessness, courage and perseverance in the fight against the harsh arctic nature. The completion of the inventory, undertaken by two detachments from different sides of the Taimyr Peninsula, was succeeded by the navigator S. Chelyuskin only seven years after the first attempts.

From the Yenisei, the Taimyr Peninsula began to be described in 1738 by navigators F. Minin and Sterlegov. The first two years they worked at the mouth of the Yenisei. At the end of the winter of 1740, Sterlegov on dogs along the coast reached a latitude of 75 ° 20 ′, later named after him, and in summer Minin reached the latitude of 75 ° 15 ′ on a boat. Then he was not allowed ice. On the east side, a detachment of Lieutenant V. Pronchishchev was sent to assault the Taimyr Peninsula. Navigator S. Chelyuskin was part of it.